Why Central Bankers Are Unsure Whether They've Raised Rates Enough

Why Central Bankers Are Unsure Whether They’ve Raised Rates Enough

At Jackson Hole, they expressed an uneasy optimism about whether rates have reached summit in battle vs inflation

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde, Bank of Japan Gov. Kazuo Ueda and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at this year’s Jackson Hole economics symposium in Wyoming.

Photo: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg News

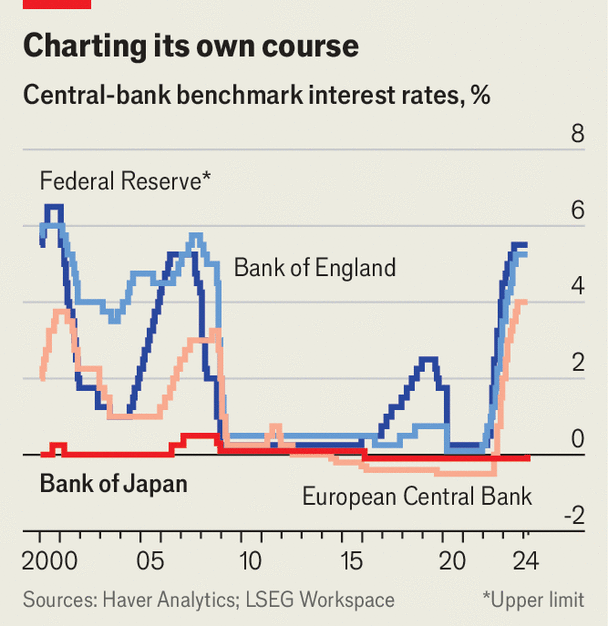

JACKSON HOLE, Wyo.—Central bankers from around the world are finally getting the inflation slowdown they have long been expecting, but worry it won’t last.

That apprehension explained the uneasy optimism underlying their discussions here in the Wyoming mountains this weekend about whether interest rates have reached a summit.

Federal Reserve officials are grappling with new economic crosscurrents. U.S. consumer spending has grown faster than they expected in recent months, buoyed by higher inflation-adjusted wages. Stronger demand prompted concerns that it might prevent inflation from falling further.

But a recent surge in long-term government bond yields combined with weakening growth abroad—could help touch off the U.S. economic slowdown that Fed officials have tried to engineer by raising rates aggressively over the past 18 months. That could help sustain inflation’s descent.

“We are very close to a good point, and then we’ll let the economy tell us” how long to keep rates high, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said in an interview Saturday that summed up two days of presentations, discussions, dinner-table conversation and hiking.

Kristin Forbes, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, compared the job facing central bankers to hiking a mountain where the trail disappears above the tree line.

“You know where you want to go. You know where the summit is, but there are no more markers and you have to feel your way,” Forbes said in an interview. “And even though you’ve covered most of the distance, that can be the hardest part. It’s steeper. It’s rockier.”

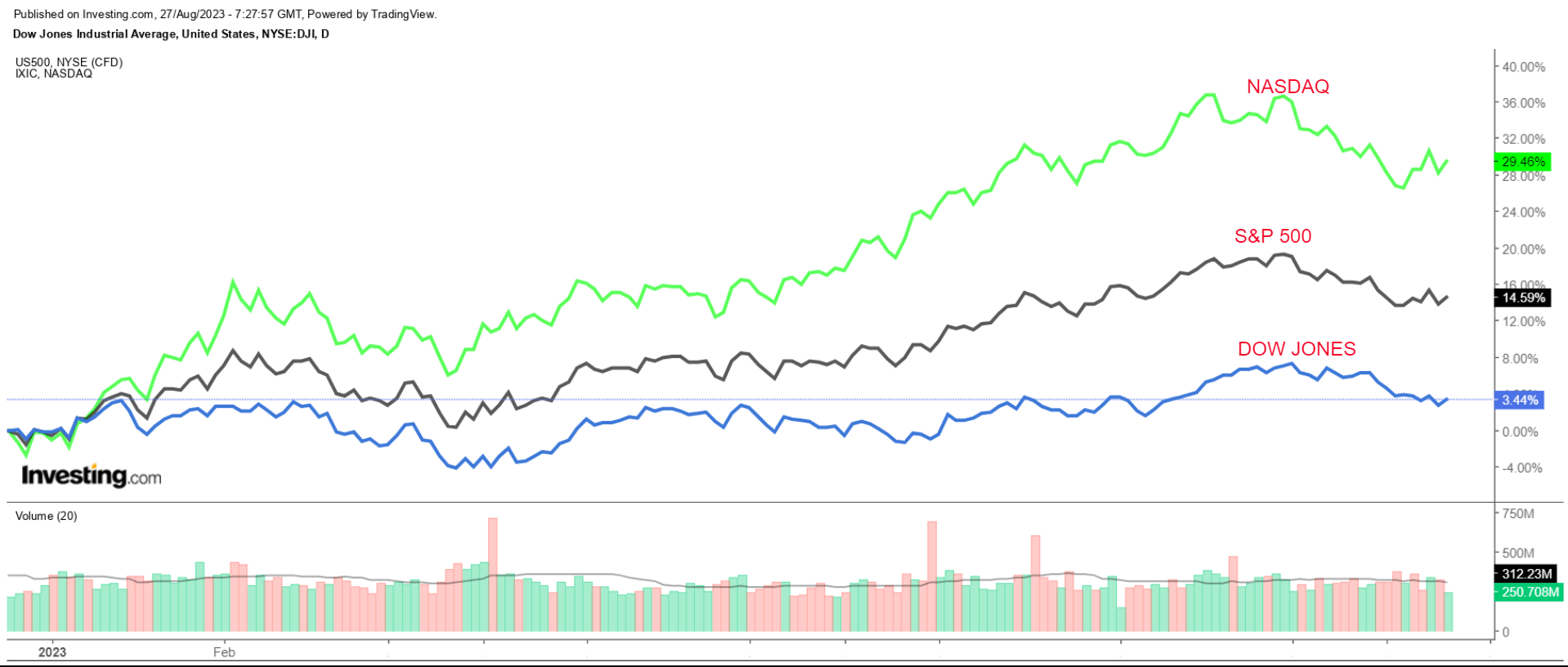

Fed officials lifted their benchmark federal-funds rate last month by a quarter-percentage-point to a range between 5.25% and 5.5%, a 22-year high. In June, most officials thought they would raise it by another quarter point this year. The Fed’s next meeting is Sept. 19-20.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell

said Friday the central bank could “proceed carefully,” implying officials would hold rates steady next month and decide whether to raise them again at their meetings in November or December.Mester said she was evaluating how and whether the higher bond yields would offset strong consumer spending. She thinks the Fed will probably have to raise rates once more, “but it doesn’t have to be in September,” she said. “We have to let this play out.”

Mester thought that after another increase this fall, Fed officials most likely could hold rates steady through next year. That would restrain activity by boosting inflation-adjusted or “real” rates as long as inflation falls.

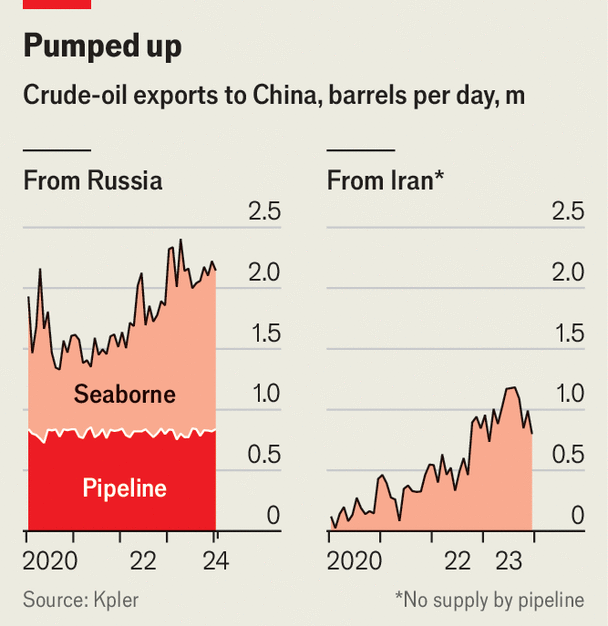

Other policy makers highlighted the potential for a slowdown in China’s property sector to create a bigger downturn in the world’s second largest economy and a major global trade partner. “The pace of economic activity in China has been a disappointment,” said Bank of Japan Gov. Kazuo Ueda on Saturday.

U.S. inflation has retreated from a 40-year high of 9.1% in June 2022. The consumer-price index rose 3.2% in the 12 months through July this year. Core prices, which exclude volatile food and energy categories, increased just 0.2% on a monthly basis in June and July, extending a broad slowdown in price pressures.

Reducing annual inflation all the way to the 2% rate seen before the pandemic could be more difficult if workers’ rapid income growth is primarily responsible for strong demand or companies raising consumer prices to cover those costs. That could require a sharper slowdown in hiring to bring down inflation.

“The hardest part now is bringing down domestic services inflation and wage inflation,” said Forbes, a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee. “It looks like things are heading in the right direction. The challenge is will it continue to head in that direction for long enough?”

Officials are also trying to understand how their past policy moves could slow the economy going forward. In a ballroom under elk-antler chandeliers, central bankers debated new research on the impact of higher rates on technology-intensive spending, including venture capital investment. The paper suggested such “innovation activities” could be more sensitive than some other sectors to higher interest rates.

“If everything becomes like the service sector and is not interest-rate sensitive, then our job just got a lot harder,” said Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee. But if newer, innovation-intensive investments are in fact more sensitive to higher rates, the Fed can more easily slow economic activity, he said.

Officials stressed they are trying to strike the right balance between raising rates too little and too much. “There’s a risk that we’ve underdone this [and] we have to go further” because the inflation problem “is just bigger than we thought,” Ben Broadbent, deputy governor of the Bank of England, said during a closing panel discussion Saturday. “There’s also a risk that we’ve already done not just enough but too much.”

Already, central bankers are facing calls from some lawmakers and economists to tolerate modestly higher inflation as they wage the potentially most difficult part of their inflation battle. Once inflation falls to 3%, they won’t get accolades for achieving their 2% inflation targets if they cause a recession.

“The political pressures that we can be under are tremendous,” said Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, while gesturing to Powell during a lunchtime session Friday.

Jacob Frenkel, former governor of the Bank of Israel, urged them not to entertain a higher inflation target by comparing such a change to a famous declaration by former Sen. George Aiken (R., Vt.) about how the U.S. might end the Vietnam War.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Do you think the Fed has taken the right steps to bring down inflation? Join the conversation below.

“Let’s not follow Sen. Aiken from 1966, declare victory, and retreat from Vietnam,” he said. (Central bankers and economists were forced to retreat during a three-mile hike in Grand Teton National Park on Friday, when a downpour including thunder and hailstones turned hiking trails into muddy streams).

Both Powell and Lagarde rejected calls to change inflation targets. Instead, the conversation on the conference sidelines focused on whether inflation might slow enough to hit 2% over several years. “It has to be timely, and it has to be sustainable,” said Lagarde. “How do you define ‘timely’ is obviously complicated.”

The process would take longer if economies are hit with new inflationary shocks that drive up prices and potentially wages. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, sent energy and grain prices surging, adding to the price pressures caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. “Maybe just one of those on its own wouldn’t have had as big an effect,” said Forbes.

Lagarde and Ueda warned that inflation could become more volatile if economies face such shocks together with a retreat of globalization that creates less flexible supply chains and limits the labor supply.

Because inflation has been very elevated for 2½ years, Mester said she still saw a greater risk of raising rates too little and allowing high inflation than in lifting them too much and forcing the economy into a needlessly severe downturn.

“I would probably opt for doing an extra [rate increase], and then if it turns out the economy” is slowing faster than anticipated, “I’d be more willing and flexible with bringing [rates] down sooner than I thought,” she said.

Write to Nick Timiraos at Nick.Timiraos@wsj.com

-(1).jpg)

-(1).jpg)

-(1).jpg)

Comments 0